If you are even remotely interested in history, genealogy or books, and you happen to find yourself in the Washington, D.C., area, you must make time for a visit to the Library of Congress (LoC). This post is meant to guide first-time visitors to the main facility in general and the Local History and Genealogy Reading Room, specifically. I hope to delve more deeply into some of the LoC’s specific resources in future posts.

The Local History and Genealogy Reading Room of the LoC is located in the Thomas Jefferson Building, Room LJ-G42, 101 Independence Avenue, SE, Washington, D.C. 20540-4660. It is within walking distance of the Capital South Metro Station. The facility is open Monday, Wednesday and Thursday from 8:30 a.m. to 9:30 p.m.; and Tuesday, Friday and Saturday from 8:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. It is closed Sundays and federal holidays.

This past August, I visited the Library of Congress to check out a book on my ancestors that I knew was in the LoC’s holdings. Before requesting to see the book, I decided to attend a free class on using genealogical resources at the LoC. These 1.5-hour orientation classes are usually held twice a month, on Wednesday mornings, and are infinitely helpful if you plan to do research at the LoC and in the reading room.

On arrival at the LoC, you must pass through security (rules: http://www.loc.gov/rr/genealogy/begin.html) and apply for a reader card that gets you access to the reading rooms and materials. This process took me less than half an hour.

Librarian Reginald Downs was the leader of the orientation session that I attended. In addition to telling us about the resources available and the protocols for requesting and using materials, he took us on a walking tour of the LoC, including the main reading room and several of the alcoves that would be of interest to genealogists/historians (the original card catalog and the city telephone directory rooms included). Reginald also briefly covered some of the other reading rooms that might be of help to historians/genealogists, including the map collection, the manuscripts reading room, the newspaper/current periodicals reading room and the rare book and special collections reading room.

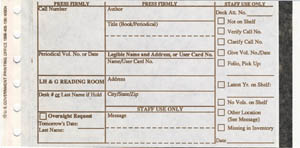

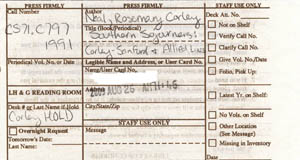

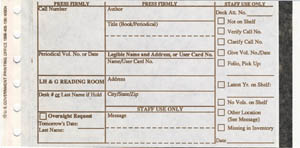

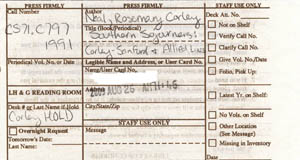

When you locate a volume at the LoC that you would like to view, you fill out a call slip and give it to a staff member in the reading room. Once you are an established user, you can request materials ahead of time online when you locate materials in the catalog before you arrive (tips for searching the catalog: http://www.loc.gov/rr/genealogy/tips.html). It takes about 45 minutes to one hour for materials to be brought to you at the room. You can write “HOLD” on the slip and your material will be set aside for you, allowing you to visit another part of the facility in the meantime (perhaps another reading room, or there are two cafeterias inside the facility that both offer pretty good food).

The reading room has desks available for your day’s research. If your work will take several days to complete, you can request a shelf or room for long-term purposes. Use reserved slips to hold the materials you are working on (this is advisable, because once you return a volume, it can take up to 7-10 days to be re-shelved and, therefore, requested again). You must use your reserved space and materials at least once a week in order to maintain it.

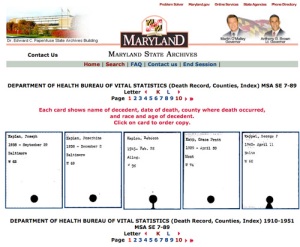

In addition to desk space where you can spread out the materials you are working with, the reading room also has computers where you can access the LoC’s subscription databases (including Ancestry Library Edition and HeritageQuest Online, among others) and the Internet. Printing from the computers is free. Copying pages from books, on the other hand, requires the purchase of a copy card for use at the reading room’s copier for $.20 per copy. Professional copying services are available at the LoC as well.

Stay tuned for more details on using specific resources in the reading room in future posts.

If you have published a genealogy, the LoC wants a copy! Learn how to donate materials and help future researchers here: http://www.loc.gov/rr/genealogy/gifts.html

You must be logged in to post a comment.